From 1 piece to mass production, our one-stop custom services ensure a worry-free experience for you.

Help Center

Views: 222 Author: Rebecca Publish Time: 2026-01-15 Origin: Site

Content Menu

● 3D Prototyping vs Traditional Prototyping

● Core 3D Prototyping Technologies

>> FDM (Fused Deposition Modeling)

>> SLS (Selective Laser Sintering)

● Industries Using 3D Prototyping

>> Aerospace

>> Healthcare

>> Automotive

>> Jewelry and Consumer Products

● Step‑by‑Step 3D Prototyping Process

>> 2. Digital Pre‑Processing (Slicing)

>> 3. 3D Printing and Post‑Processing

>> 4. Inspection, Testing, and Iteration

● Key Considerations Before Starting a 3D Prototyping Project

>> File Formats and Data Quality

● Advantages of 3D Prototyping

>> Time Savings

>> Functional Prototype Testing

● Limitations and Challenges of 3D Prototyping

>> Limited Material Options Compared to Traditional Methods

>> Build Volume and Size Constraints

>> Scalability for Mass Production

● Best 3D Printing Materials for Prototypes

>> PLA (FDM)

>> TPU

● Practical 3D Prototyping Tips for Better Results

● When to Outsource 3D Prototyping to a Manufacturing Partner

● Where to Add Visuals for Better UX

● Call to Action: Turn Your Ideas into Functional 3D Prototypes

● FAQs

>> Can I make a prototype with a 3D printer?

>> What are the main benefits of 3D prototyping?

>> Is rapid prototyping the same as 3D printing?

>> How do I choose the right 3D printing process for my prototype?

>> Which file format should I use for 3D prototyping?

3D prototyping has become a critical engine for modern product development, helping brands shorten time-to-market, reduce risk, and launch better products with fewer iterations. This in-depth guide explains what 3D printing is, how it works, when to use it, and how to choose the right process, materials, and manufacturing partner for your project.

3D prototyping is a rapid product development process in which a three-dimensional part is built directly from a digital CAD file using additive manufacturing (3D printing) technologies. Instead of cutting material away (subtractive), 3D printers build parts layer by layer to create complex shapes with minimal waste.

Key characteristics of 3D prototyping include:

- Layer-by-layer additive build process.

- Direct fabrication from CAD data (no dedicated tooling).

- Ability to create complex internal geometries and organic shapes.

- Suitability for both visual models and functional testing parts.

Because it removes traditional tooling and setup, 3D prototyping is widely used in early design validation, functional testing, and low-volume production for multiple industries.

Traditional prototyping (e.g., CNC machining, soft tooling, or manual fabrication) can be slow and expensive, especially when many design iterations are required. 3D prototyping significantly compresses this cycle by allowing designers to modify a CAD file and print a new version in hours or days.

| Aspect | 3D Prototyping (3D Printing) | Traditional Prototyping (Machining, Tooling) |

|---|---|---|

| Tooling requirement | No hard tooling; prints directly from CAD file. | Requires molds, jigs, fixtures, or set‑up tooling in many cases. |

| Design iteration speed | Very fast; easy to iterate multiple versions in short time. | Slower; each iteration often needs new tooling or set‑up. |

| Geometric complexity | Excellent; supports complex internal channels and organic shapes. | Limited by tool access and machining constraints. |

| Material waste | Low, because material is added only where needed. | Higher, especially with subtractive processes (cutting material away). |

| Unit cost at low volumes | Very competitive for 1–100+ pieces. | Often high unless volumes justify tooling investment. |

| Surface finish & accuracy | Depends on technology (FDM, SLA, SLS, etc.); can be high with post‑processing. | Typically excellent with precision machining and polishing. |

| Suitability for mass prod. | Best for prototypes and low volumes; limited efficiency for very high volumes. | Ideal when volume is high enough to amortize tooling and setup. |

Used strategically, 3D prototypes complement CNC machining, injection molding, and other traditional processes rather than completely replacing them.

Choosing the right 3D printing process is essential for a successful prototype. Each technology balances speed, accuracy, cost, and material performance differently.

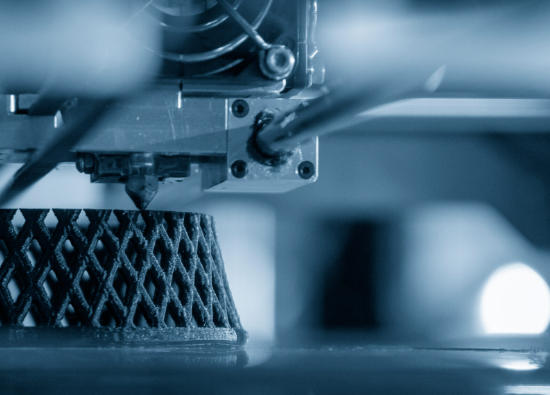

FDM is the most common and cost-effective 3D printing method for basic prototypes.

- Uses thermoplastic filaments (such as PLA, ABS, PETG) extruded layer by layer.

- Ideal for concept models, simple fixtures, and early functional testing.

- Advantages: Low cost, easy operation, wide material availability.

- Limitations: Visible layer lines, lower detail and accuracy than SLA or SLS.

SLS uses a laser to fuse plastic or metal powder in a powder bed to create dense, durable parts.

- Excellent for functional prototypes requiring good strength and mechanical performance.

- No support structures needed because unused powder supports the part during printing.

- Common materials include Nylon PA12 and other engineering plastics.

- Ideal for complex assemblies, snap‑fits, housings, and lightweight structural parts.

SLA cures liquid photopolymer resin with a UV laser to produce high‑resolution parts.

- Offers very fine details and smooth surfaces, similar to injection-molded plastic.

- Ideal for visual prototypes, precise enclosures, and parts with fine features.

- Works with specialized resins (standard, tough, heat-resistant, clear).

- Less suited for heavy mechanical loads compared to some SLS or machined parts.

3D rapid prototyping is now embedded in workflows across many sectors, from early concept validation to pre‑production testing.

- Lightweight, high‑strength components benefit from advanced lattice structures and optimized geometries.

- Prototypes for ducts, brackets, housings, and aerodynamic parts enable faster design validation.

- Helps reduce development time and material usage while meeting strict performance targets.

- Customized medical devices, surgical guides, and patient‑specific implants rely heavily on 3D printing.

- Anatomical models based on medical imaging assist surgeons in preoperative planning and training.

- Enables personalized treatment at lower cost and shorter lead times for low‑volume products.

- Used for design mock‑ups, dashboard components, brackets, and custom fixtures.

- Shortens development cycles by allowing quick fit, form, and function testing.

- Supports customization and small-batch production for performance and aftermarket parts.

- Excellent for lightweight frames, sensor housings, and internal mounting structures.

- Design teams explore complex geometries and integrate multiple functions into a single printed part.

- 3D printing lets designers produce intricate patterns and customized designs impossible with traditional methods.

- SLA and casting resins are frequently used to create masters for investment casting of fine jewelry.

A robust 3D prototyping workflow usually follows four main stages, from CAD modeling to inspection and iteration.

Every 3D prototype begins with a precise 3D model created in CAD software.

- Ensure correct overall dimensions, wall thicknesses, and geometric tolerances.

- Align material and process choices with design goals (visual vs functional).

- Common export formats: STL, OBJ, AMF, 3MF, each with different capabilities.

Practical tip: Use design guidelines for the chosen process (minimum feature size, hole diameter, overhang limits) to avoid non-printable geometry.

The CAD model is imported into slicing software, which converts it into machine instructions.

- Slicing tools (e.g., Cura, PrusaSlicer, Simplify3D) divide the model into hundreds or thousands of layers.

- Key parameters include:

- Layer height (detail vs speed).

- Infill density and pattern (strength vs material use).

- Print speed and support strategy.

Material selection (PLA, ABS, PETG, Nylon, resin, etc.) at this stage directly affects mechanical performance and surface quality.

Once sliced, the file is sent to the printer via USB, Wi‑Fi, or SD card, and the additive build begins.

- The printer deposits or cures material layer by layer until the full part is built.

- After printing, parts often require post‑processing, such as:

- Support removal and cleaning.

- Sanding, media blasting, or tumbling for smooth surfaces.

- Painting, powder coating, or clear coating for appearance and durability.

For metal or high‑performance polymer prototypes, further finishing, machining, or coating may be applied depending on the application.

Inspection is essential to confirm that the prototype meets the design intent and functional requirements.

- Dimensional checks and tolerance verification (using calipers, CMM, or 3D scanners).

- Functional testing under expected use conditions.

- User feedback and stakeholder evaluation for ergonomics and aesthetics.

Because 3D printing is highly iterative, engineers can quickly adjust the CAD model and repeat the cycle until performance targets are met.

Several technical and business factors determine whether the prototype delivers real value.

Material choice directly impacts prototype strength, flexibility, cost, and appearance.

Important aspects include:

- Price: Start early iterations with lower‑cost plastics, then move to metals or engineering polymers for final functional tests.

- Mechanical properties: Strength, stiffness, impact resistance, and fatigue behavior.

- Accuracy and surface quality requirements for mating parts or visible components.

Different materials also have specific design rules (minimum wall thickness, overhangs, feature sizes), which must be respected to avoid failures.

The intended use of the prototype guides technology and material decisions.

- For cosmetic prototypes that must match final product appearance, high‑resolution processes like SLA and fine finishing are preferred.

- For functional prototypes subjected to load or environmental stress, SLS and strong thermoplastics (e.g., PA12, reinforced polymers) may be better.

Each technology—FDM, SLA, SLS, Polyjet—has different build characteristics, material options, and design constraints.

- SLA and Polyjet are excellent for smooth surfaces and detailed features.

- SLS and FDM are robust choices for functional parts, fixtures, and test components.

Matching the process to the application is essential for reliable performance and cost control.

- STL is the most widely used 3D printing file format, but other formats like 3MF and AMF can store more metadata (colors, materials).

- Models should have a single closed shell, no unshared edges, and clearly defined units to avoid build errors.

High‑quality CAD data reduces rework and ensures that printed parts accurately reflect design intent.

3D prototyping offers several powerful business and engineering advantages over traditional methods.

- Easily supports multiple design iterations without new molds or tooling.

- Enables features that are impossible or uneconomical with conventional manufacturing, such as internal channels and lattice structures.

- Allows designers to combine multiple materials and colors in certain processes for more realistic prototypes.

- Eliminates or postpones tooling costs (e.g., injection molds) during early development stages.

- Requires only a few machines and operators to produce prototypes, making small batches economically feasible.

- Minimizes material waste due to the additive nature of the process.

- Shortens lead times from weeks to days by bypassing mold fabrication and tooling.

- Supports in‑house, on‑demand production of prototypes for immediate testing.

- Accelerates overall product development and shortens time-to-market.

- Modern materials allow creation of advanced functional prototypes close to final product performance.

- Designers can test physical parts with customers and investors before committing to large production runs.

- Early testing reduces risk and provides a competitive edge in fast‑moving markets.

Despite its strengths, 3D prototyping has limitations that must be understood to avoid incorrect expectations.

- Many standard prototyping materials (like PLA or basic resins) lack the temperature resistance or long‑term durability required for demanding applications.

- High‑performance materials (e.g., engineering polymers, advanced resins, or metal powders) can be more expensive and may require specialized equipment.

- Most desktop and many industrial printers have finite build volumes, limiting the maximum part size.

- Oversized parts must be split into multiple sections and assembled, which can affect structural integrity and aesthetics.

- For very high‑volume production, traditional processes like injection molding remain more cost‑effective once tooling is in place.

- 3D printing is best viewed as a powerful tool for prototyping, pilot runs, and complex or customized parts rather than a universal replacement for all manufacturing.

Selecting the right material is critical to achieving reliable and meaningful test results.

- White plastic powder used in SLS for robust, precise parts.

- Offers excellent mechanical properties and is suitable for both prototypes and small production runs.

- Good combination of strength, detail, and surface finish for engineering applications.

- Grey nylon material used in HP Multi Jet Fusion systems.

- Provides abrasion‑resistant, scratch‑resistant parts, and is stable under UV and outdoor conditions.

- Well‑suited to functional prototypes and end‑use parts that need reliable performance.

- Ideal for finely detailed, non‑functional prototypes and visual models.

- Produces smooth surfaces that closely resemble injection‑molded plastic.

- Best for show models, ergonomic studies, and design reviews where appearance is critical.

- User‑friendly filament with high stiffness and low warping.

- Inexpensive and suitable for concept models, fixtures, and simple functional tests.

- Good choice when aesthetics and fine detail are important at low cost.

- Flexible plastic with rubber‑like elasticity and high strength.

- Perfect for prototypes that must bend or compress, such as seals, cushions, or protective elements.

- Suitable for both prototyping and some final parts where flexibility is required.

To maximize ROI and avoid common pitfalls, engineering teams should follow a few practical guidelines.

- Start with simple concepts: Validate core geometry and ergonomics with lower‑cost materials and processes, then move to advanced materials for functional testing.

- Document process settings: Keep a detailed log of printers, materials, layer heights, and post‑processing steps to reproduce successful builds.

- Involve manufacturing early: Align with downstream manufacturing methods (such as CNC machining or injection molding) to reduce redesign work later.

- Iterate frequently: Use fast 3D print cycles to test multiple design options in parallel, especially for critical features.

Working with a specialized 3D printing service provider is often more efficient than building all capability in‑house.

A strong partner can provide:

- Access to multiple technologies (FDM, SLS, SLA, Polyjet) and a wide material portfolio.

- Professional engineering support on design for manufacturability and material selection.

- Scalable capacity for urgent prototype orders and low‑volume production.

RapidDirect, for example, offers in‑house 3D printing, extensive materials, and various post‑processing options for global customers who need fast, high‑quality prototypes.

For companies that also require CNC machining, metal stamping, plastic molding, or silicone parts alongside 3D printed prototypes, choosing an integrated OEM partner simplifies vendor management and speeds up the overall development cycle.

To enhance readability and engagement, consider adding visuals at the following points:

- A process flow diagram under “Step‑by‑Step 3D Prototyping Process” to show CAD → Slicing → Printing → Post‑processing → Testing.

- Comparison images or a table graphic in “3D Prototyping vs Traditional Prototyping” highlighting cost and time differences.

- Close‑up photos of FDM, SLA, and SLS parts in “Core 3D Prototyping Technologies” to show surface quality and detail levels.

- Material samples and application images in “Best 3D Printing Materials for Prototypes” (e.g., PA12 housings, TPU flexible parts).

- A short video or animation demonstrating layer‑by‑layer printing for visitors unfamiliar with 3D printing basics.

These visuals guide readers through complex concepts and strengthen perceived authority and trust.

Effective 3D prototyping reduces risk, cuts development costs, and helps your brand launch better products in less time. To move from concept to market‑ready design, collaborate with a manufacturing partner that can provide 3D printing together with CNC machining, plastic injection, silicone molding, and metal stamping when you are ready for mass production.

Upload your CAD files, share your requirements, and start your next 3D prototyping project today to accelerate your product development pipeline.

Yes, 3D printers are ideal for producing prototypes directly from CAD models, enabling rapid testing of shapes, fits, and functions before investing in production tooling. They support complex geometries and allow multiple iterations at relatively low cost.

Key benefits include faster design cycles, reduced tooling costs, minimal material waste, and the ability to create complex, customized parts. Together, these advantages help teams bring products to market more quickly and with fewer design errors.

Rapid prototyping is a broader term describing fast fabrication of physical models using methods like 3D printing, CNC machining, or soft tooling. 3D printing is one of the most widely used rapid prototyping technologies because of its flexibility and speed.

The best process depends on your priorities: FDM is excellent for low‑cost concept models, SLA for detailed visual parts, and SLS for durable functional components. Consider required strength, surface finish, accuracy, and budget when deciding.

STL is the most common format and is supported by nearly all printers and slicing software. More advanced formats like 3MF and AMF can store additional information such as colors and materials for complex projects.