From 1 piece to mass production, our one-stop custom services ensure a worry-free experience for you.

Help Center

Views: 222 Author: Rebecca Publish Time: 2026-01-29 Origin: Site

Content Menu

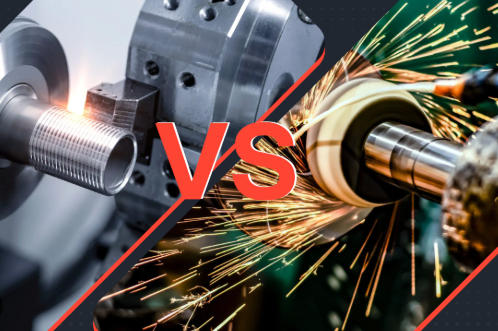

● What Are Cutting Speed and Feed Rate in CNC Machining?

● Why Feed Rate and Cutting Speed Matter for OEM and Brand Owners

● Core Differences: Feed Rate vs Cutting Speed

>> Key Concept Comparison Table

● What Is Cutting Speed in CNC Machining?

● What Is Feed Rate in CNC Machining?

● How Feed Rate and Cutting Speed Interact in Real Machining

● Factors That Affect Optimal Feed Rate and Cutting Speed

● Practical Troubleshooting: What to Adjust and When

● Feed Rate vs Cutting Speed in High-Precision OEM Parts

● A Step-by-Step Workflow to Set Feed Rate and Cutting Speed

● Case-Style Example: Small Parameter Changes, Big Impact

● Quick Reference: Feed Rate vs Cutting Speed Impact Matrix

● FAQ: Feed Rate vs Cutting Speed in CNC Machining

>> Q1: How do I know if my supplier is using proper feed rate and cutting speed?

>> Q2: Is it safe to always run at the highest recommended cutting speed?

>> Q3: Why do prototype and mass-production runs often use different feeds and speeds?

>> Q4: Does feed rate or cutting speed matter more in plastics and soft materials?

>> Q5: How often should feeds and speeds be reviewed on a long-term project?

As an overseas OEM partner, you cannot afford scrap, delays, or unstable quality. Mastering feed rate vs cutting speed is one of the simplest ways to stabilize machining quality and reduce cost per part. This guide explains these two parameters in depth, shows you how they work together, and gives you practical frameworks you can use when working with suppliers like U-NEED or managing your own CNC production.

Cutting speed is the speed at which the cutting edge of the tool moves across the material surface, usually expressed in meters per minute (m/min) or surface feet per minute (SFM). It mainly depends on tool material, workpiece material, and coating, and directly affects heat generation, tool wear, and surface finish.

Feed rate is how fast the tool advances into the workpiece, expressed in mm/min, inches/min, or mm per revolution/tooth. It controls chip thickness (chip load), cutting forces, and actual cycle time more than cutting speed does.

Choosing the right combination of feed rate vs cutting speed impacts four key aspects that matter to buyers and engineers:

- Dimensional accuracy and tolerance stability.

- Surface finish quality, including roughness, visible tool marks, and polishability.

- Tool life and downtime caused by tool changes or breakage.

- Overall part cost and lead time through cycle time optimization.

If cutting speed is too high or feed is too low, tools tend to rub instead of cut, heat rises, and surfaces may burn or harden. If feed is too high or speed is too low, cutting forces increase sharply, the machine can chatter, and delicate geometries like thin walls, slots, and micro-features become unstable.

| Aspect | Cutting Speed | Feed Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Core definition | Surface speed of the tool's cutting edge over the workpiece | Linear or per-revolution speed at which the tool advances into the material |

| Typical units | m/min, SFM | mm/min, in/min, mm/rev, mm/tooth |

| Main function | Optimizes tool-material interaction and heat generation | Controls chip load, cutting force, and material removal rate |

| Primary influence | Tool wear, thermal load, surface finish | Cycle time, chip thickness, risk of chatter or tool breakage |

| Too high | Excessive heat, rapid wear, built-up edge | Tool overload, chatter, dimensional errors |

| Too low | Inefficient cutting, rubbing, work hardening on some metals | Rubbing instead of cutting, poor finish, heat from friction |

For CNC users, the smart approach is to treat cutting speed as the starting point based on material and tool data, then tune feed rate to get the desired chip load and cycle time.

Cutting speed describes how fast the tool tip travels relative to the workpiece surface, and it is the foundation for calculating spindle RPM.

Typical cutting speed ranges by material (carbide tool, general-purpose machining):

| Material | Cutting Speed (m/min) | Cutting Speed (SFM) | Practical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum alloys | 150 – 300 | 500 – 1000 | Can run very fast with carbide, keep chips cleared. |

| Mild or low-carbon steel | 30 – 50 | 100 – 165 | Increase with coated carbide and stable setup. |

| Stainless steel | 20 – 40 | 65 – 130 | Needs good coolant to avoid work hardening. |

| Tool steel (annealed) | 20 – 35 | 65 – 115 | Reduce further for hardened conditions. |

| Brass | 90 – 200 | 300 – 650 | Machines cleanly at high speed. |

| Bronze | 60 – 120 | 200 – 400 | Adjust by alloy; some grades are gummy. |

| Cast iron | 20 – 60 | 65 – 200 | Gray iron can run faster than ductile iron. |

| Plastics such as Nylon, ABS | 100 – 200 | 325 – 650 | Avoid melting; combine moderate speed with sharp tools. |

| Titanium alloys | 20 – 30 | 65 – 100 | Low speed, rigid setup, abundant coolant. |

These values are starting points. Production conditions, tooling grade, and part geometry will shift the optimal window.

Feed rate can be defined as either linear feed (mm/min, in/min) or feed per tooth (mm/tooth, inch/tooth). The most important concept for both machinists and engineering buyers is chip load per tooth, which tells you how much material each flute removes on each revolution.

Typical feed per tooth ranges by material:

| Material | Feed per Tooth (mm/tooth) | Feed per Tooth (inch/tooth) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum alloys | 0.05 – 0.15 | 0.002 – 0.006 | Rigid setups can support higher chip loads. |

| Mild steel | 0.04 – 0.12 | 0.0015 – 0.005 | Reduce for small-diameter tools. |

| Stainless steel | 0.03 – 0.10 | 0.001 – 0.004 | Use moderate feeds to limit work hardening. |

| Tool steel (annealed) | 0.03 – 0.08 | 0.001 – 0.003 | Use lower range for finishing passes. |

| Brass | 0.05 – 0.15 | 0.002 – 0.006 | Can handle aggressive feeds. |

| Bronze | 0.04 – 0.12 | 0.0015 – 0.005 | Watch for deflection on gummy alloys. |

| Cast iron | 0.04 – 0.12 | 0.0015 – 0.005 | Feed depends on alloy brittleness. |

| Plastics such as Nylon, ABS | 0.05 – 0.20 | 0.002 – 0.008 | Higher feeds help avoid melting. |

| Titanium alloys | 0.03 – 0.08 | 0.001 – 0.003 | Keep chip load stable to prevent rubbing. |

Balanced feed rate allows the tool to cut rather than rub, which improves surface integrity and tool life.

Feed rate and cutting speed are not independent. Small changes in one often require adjustments in the other.

- If you increase cutting speed by raising RPM, you typically need to adjust feed to maintain a similar chip load per tooth.

- If you reduce feed rate too much while keeping RPM high, the cutter rubs, generating heat and premature wear.

- If you increase feed rate without enough RPM, chips become too thick and cutting forces spike, leading to chatter or breakage.

In production, mature machine shops use toolpath simulation and test cuts to find the sweet spot where tool life, finish, and cycle time are all acceptable.

Several variables influence what good feed and speed look like for any given job:

- Workpiece material and hardness, for example aluminum versus stainless steel versus titanium.

- Tool material and coating, such as HSS, carbide, coated carbide, or PCD for plastics.

- Tool diameter, flute length, and overhang, since long, thin tools need gentler settings.

- Machine rigidity and spindle power, from high-speed machining centers to lighter machines.

- Coolant strategy, including flood, minimum quantity lubrication, dry cutting, or through-spindle coolant.

- Feature geometry, such as thin ribs, deep pockets, micro-holes, or large open pockets.

The more delicate the geometry or setup, the more conservative your feed and speed should be, especially on first articles.

Common symptoms and first adjustments include:

- Poor surface finish: slightly reduce feed, increase cutting speed within tool limits, check tool sharpness and rigidity.

- Excessive tool wear or burning: lower cutting speed, verify coolant flow, avoid rubbing by maintaining minimum chip load.

- Chatter or vibration: shorten tool overhang, reduce feed or depth of cut, sometimes slightly increase RPM to move away from resonance.

- Burrs on edges, especially in plastics and aluminum: optimize feed to maintain a clean shearing action, use sharp tools and an appropriate exit strategy.

Professional machine shops adjust one parameter at a time, log the results, and lock in stable process recipes for each part.

As an OEM buyer, you often deal with more than just metal CNC machining. Plastic components, silicone parts, and stamped metal pieces all respond differently to feed and speed decisions.

- For precision metal machining, cutting speed and feed rate drive tolerance stability and surface finish, especially on bearing fits, sealing faces, and mating features.

- For plastic machining, speeds must be controlled to avoid melting, while feed is set high enough to cut instead of smear the surface.

- For silicone tooling and related inserts, metal inserts and mold bases rely on conservative feeds and speeds for stable cavity dimensions.

- For metal stamping tooling, CNC parameters in die manufacturing affect edge sharpness, tool life, and the quality of stamped edges.

A supplier that understands this cross-process behavior can coordinate parameters so machined, molded, and stamped parts assemble smoothly.

You do not need to be a machinist to ask the right questions and ensure your supplier uses optimized feed rate vs cutting speed. Use this workflow internally or with partners:

1. Start from material and tool data

Confirm the workpiece material grade and hardness with your supplier. Ask which tool material and coating they plan to use.

2. Define priorities for the part

Decide whether this is a prototype where flexibility matters most, or a high-volume part where cycle time and tool life are the primary concerns. Clarify critical surfaces, tolerances, and cosmetic areas in advance.

3. Use recommended ranges as a starting point

Suppliers choose cutting speeds and feeds from reference tables based on their machines and tools. Encourage them to start on the lower side for first articles.

4. Validate via machining trial or simulation

Use toolpath simulation to detect overloads, collisions, or impossible accelerations before cutting. For critical features, request a small test run or process capability data when volumes justify it.

5. Review sample results and iterate

Check dimensions, surface finish, and consistency across pieces. If results are stable, the supplier can gradually increase feed or speed to reduce cycle time.

6. Lock in the process parameters

For long-term projects, ask your supplier to document the final feed and speed parameters in the control plan or process sheet.

This approach keeps machinists and engineers aligned on both quality and commercial expectations.

Consider a batch of high-precision aluminum housings with thin walls and tight flatness requirements.

- Initial parameters: aggressive cutting speed and high feed to minimize time, selected without considering thin-wall deflection.

- Result: noticeable chatter marks, inconsistent wall thickness, and extra manual deburring.

After a process review, parameters are adjusted:

- Cutting speed is kept moderately high for clean cutting but reduced slightly to control heat.

- Feed per tooth is lowered and depth of cut reduced in thin areas, while other features retain higher feed for efficiency.

The outcome is more consistent wall thickness, improved surface roughness, and reduced deburring time. Even with a slightly longer machine cycle per part, total cost drops thanks to less rework and scrap.

This kind of optimization illustrates how professional OEM suppliers add value beyond simply running a program.

| Change | Immediate Effect | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Increase cutting speed, keep feed constant | Higher heat, smoother finish up to a point | Finishing passes on steels and aluminum |

| Decrease cutting speed, keep feed constant | Lower heat, lower material removal rate, longer cycle | Difficult materials such as titanium and stainless steel |

| Increase feed rate at same speed | Thicker chips, more force, shorter cycle | Roughing passes in rigid setups |

| Decrease feed rate at same speed | Thinner chips, risk of rubbing | Fine finishing, small tools, delicate features |

| Increase both speed and feed | High material removal, higher risk if overdone | Stable roughing on robust machines |

| Decrease both speed and feed | Very safe but slow cutting | First-article runs, unknown materials |

Use this as a mental model when discussing process changes with your machining partner.

If you are a brand owner, wholesaler, or manufacturer looking for a stable partner for high-precision machined parts, plastic components, silicone products, and metal stampings, U-NEED is ready to support you. Our engineering team evaluates every drawing, selects suitable cutting speeds and feed rates for each material and feature, and optimizes the process for both quality and cost. Send us your 2D and 3D files today, and let U-NEED provide you with reliable OEM manufacturing solutions from process planning to final delivery.

Contact us to get more information!

Ask for their base material data, tool type, and typical cutting speed and feed ranges for your material and feature size. If their values are far outside commonly used ranges, discuss the reasons and request sample data to confirm stability.

No. Very high cutting speeds can shorten tool life, increase heat, and reduce dimensional stability on thin or delicate parts. The best speed is usually a compromise between surface finish, accuracy, and tool cost.

Prototypes usually prioritize safety and flexibility, so feeds and speeds are conservative. As the process stabilizes and the supplier understands tool life and scrap rates, parameters are increased step by step to improve efficiency in mass production.

Both matter, but in plastics, controlling heat is critical. Cutting speed must be moderate, while feed needs to stay high enough to avoid rubbing and melting. Chip evacuation and tool sharpness are also very important.

Whenever there is a change in material batch, tooling brand, machine, or tolerance requirement, feeds and speeds should be checked again. For ongoing high-volume projects, periodic reviews help reduce cost through incremental optimization.