From 1 piece to mass production, our one-stop custom services ensure a worry-free experience for you.

Help Center

Views: 222 Author: Rebecca Publish Time: 2026-01-29 Origin: Site

Content Menu

● Main Types of End Mills and Their Uses

● End Milling vs Face Milling: Key Technical Differences

● Tooling Considerations: End Mill vs Face Mill

● Material Compatibility and Cutting Strategy

● Cost, Efficiency, and Cycle Time

● Tool Wear, Life, and Maintenance

● Practical 5-Step Workflow: Combining End Milling and Face Milling

● Example Use Cases in High-Precision Manufacturing

● How to Choose: A Quick Decision Guide

● FAQs About End Milling vs Face Milling

>> 1. Can I use an end mill instead of a face mill for surfacing?

>> 2. Why does my face milled surface show chatter marks?

>> 3. Which is better for stainless steel: end milling or face milling?

>> 4. When should I switch from roughing to finishing tools?

>> 5. Do I always need 5-axis machines for complex 3D parts?

If you want better surface finish, higher efficiency, and lower machining cost, you must clearly understand the differences between end milling and face milling and know when to use each in real production.

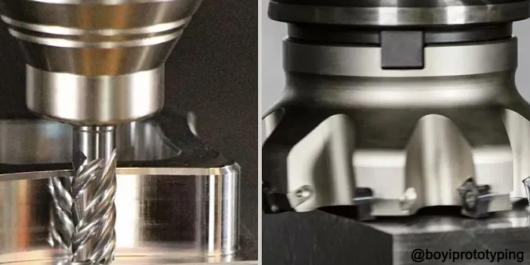

End milling is a machining process where the cutting tool enters the material perpendicularly and removes material with both the side and the tip of the cutter. This allows the tool to machine in X, Y, and Z directions for highly flexible operations.

Common operations achieved by end milling include:

- Profiling external edges and contours

- Pocketing internal cavities

- Slotting and keyway machining

- Engraving text, logos, and marks

- 3D contour finishing on molds and dies

Because of this flexibility, end milling is widely used for custom parts, complex geometries, prototypes, mold features, and post-casting refinement.

End mills look similar to drill bits but have cutting flutes along both the sides and the tip, so they can cut vertically, laterally, and diagonally. Unlike drills that mainly cut in the axial direction, end mills can perform side milling, ramping, and helical interpolation.

Key characteristics of end mills include:

- Solid carbide or HSS construction, sometimes with coatings

- Helix angle and flute count optimized for different materials

- Availability in metric and inch diameters and multiple overall lengths

For shops running a mix of materials and batch sizes, well-selected end mills are the core cutting tools for precision machining.

Different end mill geometries are designed for specific applications and materials.

- Square end mills – Flat-ended tools used for clean shoulders, flat-bottomed slots, and pocketing operations where sharp internal corners are required.

- Ball nose end mills – Hemispherical tip for 3D contoured surfaces such as molds, dies, and complex 3D profiles.

- Corner radius end mills – Slightly radiused corners to reduce chipping and extend tool life in high-stress cuts.

- Roughing (corncob) end mills – Serrated flutes to remove large volumes of material quickly during roughing.

When machining aluminum and other non-ferrous metals, dedicated end mills with polished flutes, high rake angles, and fewer flutes (typically 2–3) help evacuate chips and avoid built-up edge.

Face milling uses the bottom, or face, of the tool rather than the side to cut, and it is mainly used to create flat surfaces and rapidly remove material from large areas. The cutter is generally larger in diameter and makes shallow passes across the workpiece surface.

Typical face milling tasks include:

- Producing highly flat reference surfaces

- Squaring blocks on multiple sides

- Removing scale, stock, or allowance quickly

- Preparing raw stock for subsequent precision machining

Face milling is usually the first operation to square the block before detailed features are added.

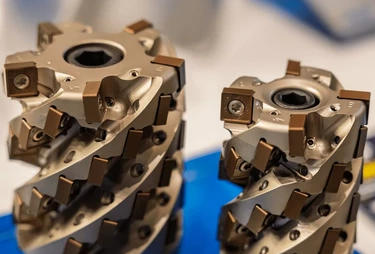

A face mill typically consists of a large-diameter cutter body with multiple indexable inserts mounted around its periphery. It is usually mounted horizontally on the spindle and run at suitable speeds and feeds for stable surfacing.

Advantages of indexable face mills include:

- Replaceable inserts instead of changing the whole tool

- Multiple cutting edges per insert for lower cost per edge

- Large effective cutting width for high material removal rate

Face mills are ideal on machines with rigid spindles and high torque, especially for steel plate, cast iron bases, and large frames.

The table below summarizes the core differences between end milling and face milling.

| Feature | End Milling | Face Milling |

|---|---|---|

| Cutting area | Sides and tip of the tool | Bottom (face) of the tool |

| Best for | Slots, pockets, contours, complex shapes | Flat surfaces, squaring, large-area surfacing |

| Tool design | Smaller diameter, solid or insert-based | Larger diameter body with indexable inserts |

| Feed direction | Often vertical and lateral (X, Y, Z) | Horizontal feed across part face |

| Material removal rate | Moderate, focused on accuracy | High, ideal for bulk stock removal |

| Surface finish | Excellent on small features and detailed areas | Excellent flatness and good overall face finish |

| Machine requirements | Vertical mills, routers, CNC machining centers | Milling machines with rigid, high-torque spindles |

A simple example: when machining a custom bracket with pocketed holes, you rely on end mills; for a flat steel plate that must be surfaced before drilling, you select a face mill.

You should prioritize end milling when:

- You need internal pockets, slots, keyways, or complex 2D or 3D contours.

- Parts include small features, tight internal corners, or narrow channels where larger cutters cannot enter.

- Accuracy on localized areas is more critical than maximum material removal rate.

- You are machining prototypes, molds, or precision components with complex geometry.

For deep cavities, steep walls, or multi-sided features, combining end mills with 5-axis CNC machining allows the tool to approach from multiple angles and maintain optimal cutting conditions.

Face milling is the better choice when the main objective is flatness, speed, and efficient stock removal.

Typical situations include:

- Squaring off raw blocks before finishing

- Surfacing large plates or frames to tight flatness requirements

- Removing casting skin or scale on steel plates

- Reducing cycle time in batch production by quickly preparing datum surfaces

In many production workflows, face milling comes first to prepare the workpiece, followed by end milling to cut details and tolerance-critical features.

The choice between an end mill and a face mill frequently depends on tool size, machine horsepower, and part geometry.

Key points:

- Face mills are usually large diameter and need a rigid spindle and plenty of torque to avoid chatter and achieve good finish.

- Small-diameter end mills can work well on lighter machines or in narrow features where the part or setup does not allow large tools.

- For tight internal corners and intricate 3D forms, end mills are essential; face mills simply cannot access these geometries.

A practical rule is to use a face mill wherever the machine and setup can support it, then switch to end mills for features that require precision or accessibility.

Both end mills and face mills can handle steel, aluminum, copper, stainless steel, and titanium, provided the cutter geometry is matched to the material.

General guidelines include:

- For aluminum, use high-helix, polished end mills or face mills with aggressive rake angles to avoid chip packing.

- For steel, coated carbide tools with optimized chip breaker designs help control heat and chip shape.

- For stainless steel, tool rigidity and sufficient coolant flow are critical to avoid work hardening and premature wear.

Proper feed rates, spindle speeds, and coolant strategy are essential for both tool types to maintain edge sharpness and part quality.

From a production cost perspective, face milling and end milling play different roles in your strategy.

- Face milling provides a higher material removal rate, making it ideal for bulk surfacing and roughing large areas.

- End milling may be slower in removing stock but can reduce finishing costs because it delivers high accuracy, allows fewer setups, and consolidates multiple operations with one tool.

One effective approach in batch production is to use a face mill to square and surface all blocks, then switch to end mills to machine pockets, slots, and details, minimizing total cycle time.

Tool life is closely tied to application, material, and cutting parameters.

- End mills tend to wear faster in hard materials and at sharp internal corners where stress concentrates.

- Face mills often have longer service life thanks to indexable inserts; when an edge wears, you simply index or replace the insert instead of changing the entire tool.

- Both benefit from correct feed, speed, and coolant management to control temperature and vibration.

Establishing a preventive tool wear monitoring routine and using wear limits for inserts can significantly stabilize part quality and uptime.

In real CNC production, the best results often come from combining both operations in a structured process:

1. Face milling for datum surfaces – Use a face mill to create flat reference faces on raw stock and remove excess material quickly.

2. Squaring and alignment – Face mill adjacent sides to obtain square blocks and reliable clamping surfaces.

3. Rough pocketing with end mills – Use roughing end mills to open pockets and cavities while leaving a small allowance.

4. Precision finishing with end mills – Apply square or ball nose end mills to finish walls, floors, and 3D contours to final tolerance.

5. Final skim pass if needed – Perform a light face milling skim to achieve the highest surface flatness on critical faces.

This workflow balances speed, accuracy, and tool life while keeping programming and fixturing manageable.

Across precision machining, plastics, silicone, and metal stamping, the following patterns are very common:

- CNC machined aluminum housings: face milling to create flat mounting surfaces, then end milling for internal cavities and threaded features.

- Mold bases and plates: face milling for plate flatness, end milling for cooling channels, pockets, and parting-line details.

- Brackets and structural parts: face milling for reference faces, end milling for slots, lightening pockets, chamfers, and profiles.

- Prototype parts: mostly end milling due to frequent design changes and complex geometries, with limited face milling as needed.

Understanding these patterns helps you choose the right strategy for OEM production, small batches, and custom projects.

Use this simplified guide when deciding between end milling and face milling for a given operation.

Choose face milling if:

- The area to machine is wide and mostly flat.

- The machine has enough spindle power and rigidity.

- Speed and flatness are higher priorities than local detail.

Choose end milling if:

- You need internal features, narrow slots, or deep pockets.

- The geometry includes 3D shapes or tight internal corners.

- Accuracy and surface quality on small areas are critical.

In many projects, the optimal solution is not “either or”, but “both in the right order”: face mill to prepare, end mill to finish.

Choosing the right balance between end milling and face milling directly influences your part quality, unit cost, and delivery time. If you want stable quality, reliable delivery, and professional process optimization, U-NEED is ready to support you. As a China-based OEM partner focusing on high-precision machined parts, plastic components, silicone products, and metal stamping, we can design the most suitable machining route for your drawings and materials, and combine face milling and end milling to achieve efficient and consistent production. Contact U-NEED today with your 2D or 3D files to get a fast, tailored quotation and start your next project with a trustworthy manufacturing partner.

Contact us to get more information!

Yes, you can surface with a large-diameter end mill, but a dedicated face mill usually offers higher material removal rate and better flatness on large areas.

Chatter usually comes from insufficient machine rigidity, incorrect feed and speed, or a cutter that is too large for the setup. Adjusting cutting parameters, improving clamping, or reducing overhang often helps.

Both can work well if the cutter geometry, coating, and coolant strategy are appropriate for stainless steel. Rigidity and heat control are more critical than the choice of operation alone.

After you remove most stock with roughing tools, such as a face mill or roughing end mill, and leave a small allowance for finishing, you should switch to sharp finishing end mills for the final passes.

No, many geometries are achievable on 3-axis machines, but 5-axis CNC allows end mills to approach from multiple directions, improving access, surface quality, and efficiency for deep or steep features.