From 1 piece to mass production, our one-stop custom services ensure a worry-free experience for you.

Help Center

Views: 222 Author: Loretta Publish Time: 2025-12-24 Origin: Site

Content Menu

● Core Surface Roughness Parameters

>> Ra – Arithmetic Average Roughness

>> Rz – Average Maximum Height

>> Rt / Rmax – Total Profile Height

● Surface Roughness Chart And Typical Values

● How Surface Roughness Is Measured

>> Contact Stylus Profilometers

>> Optical And Noncontact Methods

● Reading And Applying A Surface Roughness Chart

>> Step 2: Select A Target Roughness Range

>> Step 3: Choose Supporting Parameters

>> Step 4: Communicate Clearly On Drawings

● Standards For Surface Roughness

>> ISO 4287

>> ISO 21920 And Other Updates

● Practical Roughness Guidelines For Common Applications

>> Sliding And Rotating Components

>> General CNC Machined Metal Parts

>> Injection Molded Plastic Parts

● Case Examples Of Roughness Choices In Practice

>> Example 1: Hydraulic Valve Body

>> Example 2: Consumer Product Enclosure

● Common Mistakes When Using Surface Roughness Charts

>> Ignoring Measurement Settings

● Role Of A Professional OEM Partner

● Turn Your Surface Roughness Requirements Into Stable Production

● FAQs About Surface Roughness And Surface Finish

>> 1. What is the difference between surface roughness and surface finish

>> 2. Why is Ra used more often than other parameters

>> 3. When should I use Rz or Rt instead of only Ra

>> 4. Can I convert between Ra, Rz, and Rq using simple factors

>> 5. How does surface roughness influence coating and painting

Surface roughness is a critical factor in part performance, cost, and appearance across CNC machining, injection molding, silicone products, and metal stamping. Understanding how to use a surface roughness chart correctly helps engineers and buyers specify finishes that are both functional and economically realistic.

Surface roughness describes the microscopic peaks and valleys on a manufactured surface. It is one of the main components of surface texture, together with lay and waviness.

- Smoother surfaces improve sealing, fatigue strength, and aesthetics but are usually more expensive to produce.

- Rougher surfaces can enhance coating adhesion or lubricant retention and are often acceptable for noncritical areas.

On technical drawings, surface roughness is expressed using standardized parameters and symbols so that design teams and manufacturers can communicate clearly.

Different parameters quantify surface texture in different ways. Each one highlights specific functional risks, such as leakage, friction, wear, or cosmetic defects.

Ra is the most commonly used roughness parameter in industry.

- It represents the arithmetic average of the absolute deviations of the surface profile from the mean line over a defined sampling length.

- A lower Ra value means a smoother surface; for example, Ra 0.4 µm is smoother than Ra 3.2 µm.

Ra is widely used because it is intuitive, standardized, and easy to compare across suppliers and processes.

Rz is the average of the vertical distance between the highest peaks and lowest valleys over several sampling lengths.

- It responds more strongly to isolated scratches, burrs, or pits than Ra.

- It is frequently used in many regions for functional surfaces such as seals, sliding interfaces, and critical contact areas.

Rz is especially helpful when the risk of sharp peaks must be tightly controlled.

Rq, also called RMS roughness, is the root mean square of the height deviations from the mean line.

- It behaves similarly to Ra but is more sensitive to large deviations.

- It is often used in fields where statistical analysis is important or where legacy RMS conventions are still standard.

Rt or Rmax represents the total height between the highest peak and lowest valley within the evaluation length.

- It is useful for detecting extreme defects such as deep scratches and large burrs that might be missed by Ra alone.

- It is often specified on critical sealing or contact surfaces.

In many practical drawings, Ra is specified as the primary control, while Rz or Rt is added to prevent harmful local defects.

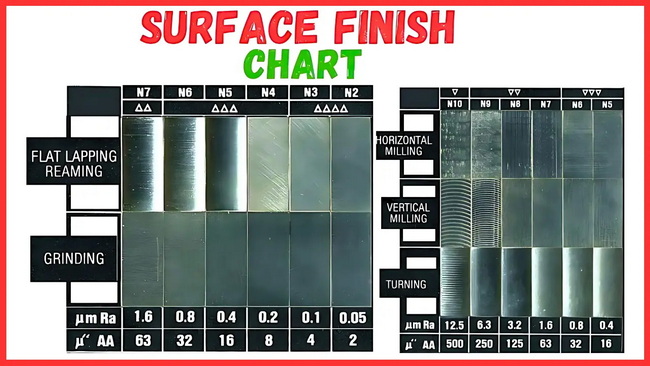

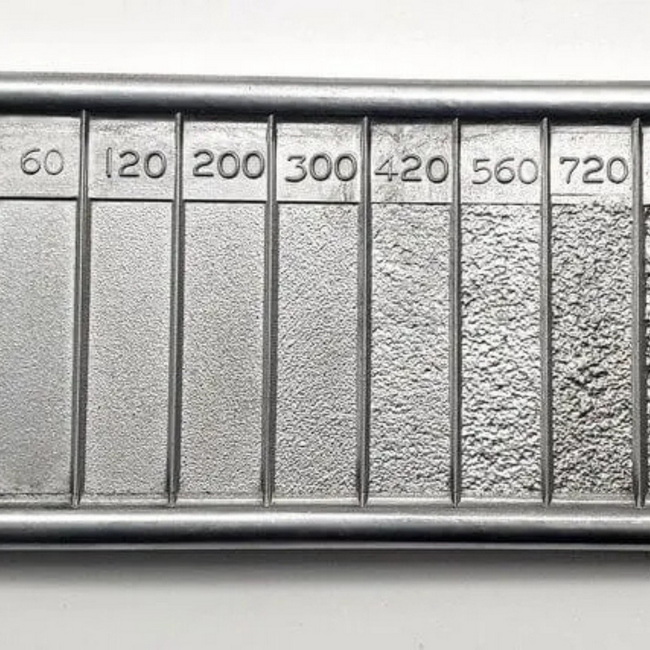

A surface roughness chart links numerical roughness values with practical process capabilities and typical finishes. This makes it easier to select a realistic surface requirement at the design stage.

Below is a representative table of common roughness levels for typical manufacturing processes. Actual values can vary by material, machine condition, and tooling.

Typical process / finish | Ra (µm) | Ra (µin) | Typical Rz (µm) | Typical applications |

Rough as-cast surface | 12.5 | 500 | ~50 | Cast housings, noncritical covers, structural brackets. |

Very rough machined surface | 6.3 | 250 | ~25 | Forgings, low-tolerance parts, internal noncritical surfaces. |

Rough turning or milling | 3.2 | 125 | 12.5 | General structural parts, prototypes, internal non-sealing zones. |

General machining finish | 1.6 | 63 | 6.3 | Standard CNC parts, frames, machine components. |

Fine machining or light grinding | 0.8 | 32 | 3.2 | Bearing seats, sliding components, visible functional surfaces. |

Precision grinding or lapping | 0.4 | 16 | 1.6 | Sealing lands, precision shafts, high-speed rotating and precision parts. |

Lower Ra and Rz values correspond to smoother finishes that support tighter sealing, lower friction, and better cosmetic appearance. Higher values are normally used where strength and cost matter more than texture.

Reliable specification is only meaningful if measurement practices are consistent. The choice of instrument and settings has a direct impact on reported values.

Stylus profilometers are widely used on shop floors.

- A diamond stylus moves across the surface and records a 2D profile of height versus distance.

- From this profile, parameters such as Ra, Rz, Rq, and Rt are calculated using standardized formulas and filters.

Cut-off length and evaluation length must be chosen correctly for the part and parameter; otherwise, two measurements of the same surface may appear different.

Optical instruments are increasingly used for precision and delicate surfaces.

- Techniques such as interferometry, confocal microscopy, and focus variation reconstruct the surface without physical contact.

- These systems are ideal for very smooth, soft, or complex surfaces where a stylus might damage the surface or miss localized features.

Noncontact methods also make it easier to capture 3D surface data, which helps when analyzing functional behavior beyond simple 2D profiles.

A surface roughness chart becomes especially useful when it is integrated into a clear design and manufacturing workflow.

First, clarify what each surface must do.

- Sealing surfaces require controlled peaks and valleys to avoid leakage.

- Sliding or rotating surfaces must balance low friction with adequate lubricant retention.

- Cosmetic surfaces focus on visual appearance and tactile feel, while purely structural surfaces often allow higher roughness.

Mapping each area of the part to one of these functions prevents over-specification.

Once functional roles are clear, select a roughness range that matches both function and process capability.

- For many precision surfaces, a range such as Ra 0.8–1.6 µm offers a good balance between cost and performance.

- Noncritical areas may tolerate Ra 3.2 µm or higher, reducing machining time and tooling wear.

Avoid specifying extreme smoothness if it is not functionally necessary, because each extra polishing step adds cost and lead time.

Relying on a single parameter can be risky.

- Combine Ra with Rz or Rt for sealing faces and wear-critical areas so that harmful peaks are controlled.

- Add parameters only where they add clear functional value; unnecessary complexity can confuse inspection and quality control.

This balanced approach ensures that specifications protect function without making measurement and acceptance criteria overly complicated.

Surface requirements should be expressed with standard symbols and text.

- Use the proper surface finish symbol, add the numerical values, and indicate the required lay direction where necessary.

- Clarify whether values represent a maximum, a minimum, or an acceptable range, for example, “Ra 0.8–1.6 µm” rather than a single number with no tolerance.

Clear drawings reduce the risk of misinterpretation, especially in international collaborations.

Surface roughness charts and parameters are tied to global standards. Understanding these standards helps align expectations between design, manufacturing, and inspection.

This standard defines common 2D profile parameters such as Ra, Rz, Rq, Rt, and many more.

- It also specifies the way the profile is filtered and evaluated.

- It has been widely used for many years, and many existing drawings and charts are still based on this system.

More recent standards modernize and refine how roughness profiles are handled.

- They adjust definitions, filters, and evaluation methods for better consistency and clearer interpretation.

- When different plants use different standard generations, measured values for the same surface may differ slightly.

Agreeing on which standard edition and settings are used avoids confusion and helps ensure that measured results are accepted on both sides.

Reasonable starting values make it easier to decide which roughness to call out for each surface type. Actual choices should always be refined based on testing, material, and process capability.

Sealing faces on valves, flanges, and covers need controlled roughness to prevent leaks.

- Typical target ranges are between Ra 0.2 µm and 0.8 µm for metal-to-metal seals and similar interfaces.

- Additional control with Rz or Rt can prevent sharp peaks that would otherwise cut into gaskets or seal rings.

Shafts, bushings, and guiding surfaces must combine low friction with good wear behavior.

- Typical ranges fall between Ra 0.4 µm and 1.6 µm, depending on speed, load, and lubrication.

- Too smooth a surface can sometimes reduce lubricant retention, while too rough a surface increases friction and wear.

A full tribological view is needed for high-speed, high-load, or safety-critical applications.

Many structural or noncritical metal components do not require very smooth finishes.

- Roughness between Ra 1.6 µm and 3.2 µm is often adequate for general features.

- These levels keep machining times reasonable while still delivering good assembly fit and acceptable appearance.

Relaxing roughness requirements on nonfunctional surfaces is one of the easiest ways to reduce part cost.

Plastic parts have very different surface behavior.

- Functional surfaces may use moderate roughness that supports assembly and friction performance.

- Cosmetic faces are controlled primarily by mold polishing and texturing grades that can be related to approximate roughness levels.

In many cases, mold finish standards are the reference for plastics, while micrometer-level parameters provide an approximate correlation.

Real-world examples show how roughness specifications influence performance and cost.

A hydraulic valve body with multiple internal channels initially used the same tight roughness requirement everywhere.

- A uniform requirement near Ra 0.4 µm significantly increased machining and finishing time.

- By identifying the true sealing lands and keeping the tight requirement only there, while relaxing other internal surfaces to Ra 1.6 µm, cost and cycle time were reduced without sacrificing function.

An electronics enclosure required a premium cosmetic appearance.

- The external surfaces were tied to specific mold polishing grades to achieve a consistent look across suppliers.

- Linking those mold finishes to a roughness chart allowed engineering and quality teams to better compare trial samples and maintain visual consistency over time.

In both cases, thoughtful use of a surface roughness chart helped adjust specifications to real functional needs.

Several recurring errors cause avoidable quality and cost problems. Recognizing them early leads to smoother projects.

Relying only on Ra can hide harmful profile shapes.

- Two surfaces may have the same Ra while one has sharp peaks and the other has gentle waves.

- Adding Rz or Rt reveals whether extreme peaks or valleys exist that might damage seals or increase wear.

Demanding very low roughness everywhere can be counterproductive.

- Each reduction in Ra generally requires additional machining, grinding, or polishing steps.

- Overly smooth surfaces may also reduce coating adhesion or lubricant retention for certain applications.

Specifications should be as tight as necessary, but no tighter.

Measurement inconsistency leads to disputes.

- Different cut-off lengths, filters, or instrument types can produce different values for the same surface.

- If these conditions are not coordinated and documented, buyer and supplier may interpret the same part differently.

Consistent measurement practice is as important as the numerical limits themselves.

A capable OEM partner with experience in high-precision machining, plastic components, silicone products, and metal stamping can turn surface roughness theory into reliable, scalable production.

- Engineering teams can recommend realistic surface targets based on process capability, material, and volume.

- Quality departments can apply standardized measurements, provide full inspection data, and help adapt specifications during prototyping.

- Project managers can support international customers with clear communication, documentation, and stable supply for long-term cooperation.

This combination of engineering expertise and process control helps ensure that surface roughness requirements are met consistently from sample to mass production.

If your current or upcoming project involves precision machined parts, plastic components, silicone products, or metal stamped parts, surface roughness requirements will directly influence performance, price, and lead time. To reduce risk and accelerate launch:

- Share your drawings and current surface finish requirements for key components.

- Request a detailed manufacturability review focused on surface roughness, process selection, and inspection methods.

- Work together with an engineering team that can suggest optimized roughness targets, choose suitable processes, and build an inspection plan that matches your quality expectations.

Take the next step now by sending your project files and requirements so that an expert team can help transform your surface roughness specifications into stable, repeatable, and cost-effective production.

Surface roughness is a quantitative description of the microscopic peaks and valleys on a surface. Surface finish is a broader concept that includes roughness, waviness, lay, and often visual and tactile qualities such as gloss and texture.

Ra is widely used because it is straightforward to calculate, well standardized, and easy to compare between different machines and suppliers. In many general applications it provides enough information when combined with process knowledge and basic visual inspection.

Rz and Rt are helpful when surfaces must avoid isolated scratches, burrs, or deep pits, such as in sealing interfaces and sliding contacts. They capture peak-to-valley variations that might still exist even when Ra looks acceptable.

Empirical conversion factors exist, but they are only approximate and depend on the actual profile shape. For critical parts, it is more reliable to measure the specific parameter directly rather than relying on conversions.

A moderate level of roughness helps coatings and paints adhere by providing mechanical anchoring. If the surface is too rough, however, coatings may show visible defects or inconsistent thickness, so the optimal range must be tuned for the coating system and application.